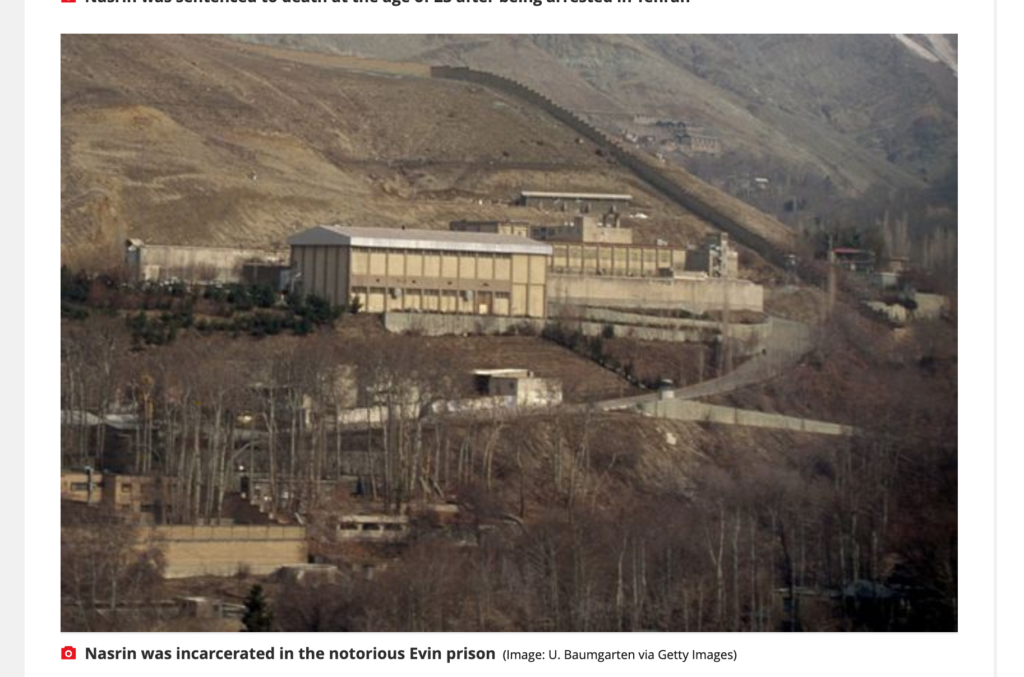

More than thirty years ago, I suffered terribly at the hands of the Iranian government. I was imprisoned for eight years, and they tried to silence me with torture. All I’d done was take to the streets to demand my freedom and liberty from an oppressive and authoritarian regime.

The torturers tried to take my voice away. And therapy, writing and art played a vital role in helping me to express myself again. When I first came to the UK, after leaving my friends and family behind, I felt lost. But I was given support by organisations like Freedom from Torture that had a transformative impact on my life. I joined Write to Life, a creative writing group for survivors of torture. Through writing I regained my voice.

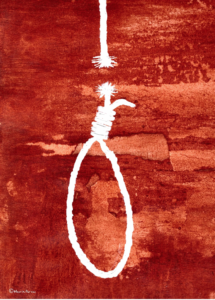

For many years writing was a means of escape for me. But art opened my eyes and I realised that it could be a way of fighting back, as well as a means of change. It can provide a counterpoint to what those in power and their media are showing to people. Art can change people’s minds. That’s why art is seen as a threat to power. Look how many artists are imprisoned in Iran from rappers, like Toomaj Salehi, to film makers and other artists.

Sharing my story through writing, and now through my art, is such a powerful way to tell difficult stories. It can give such an important insight into the very painful realities faced by those of us who’ve experienced torture. Today, I’m a member of Survivors Speak OUT (the UK’s torture survivor-led activist network) and I can raise awareness of the horrors happening in Iran. Being able to do this has helped give my life meaning since I had to leave my home.

I’ve listened and watched in terror at the violence that has swept across my country, since the death of 22-year-old Jina Mahsa Amini at the hands of the abusive “morality police” in September 2022. Although media interest is disappearing, the wave of protests sparked by Amini’s death haven’t died away, they’ve just changed. Instead of thousands taking to the streets, young people gather to dance, and women risk their lives and liberty just to sing.

Now, things like street dancing, singing, paintings and music are such an important way for people in Iran to protest. Many forms of art – like songs, digital art, videos, graffiti – have been created during the Woman, Life, Freedom revolution. Each of them emphasises protest actions, resistance, and different forms of activities against the regime’s repressive system. My own work explores personal and political journeys based on both my life and collective experiences that I have witnessed and heard about.

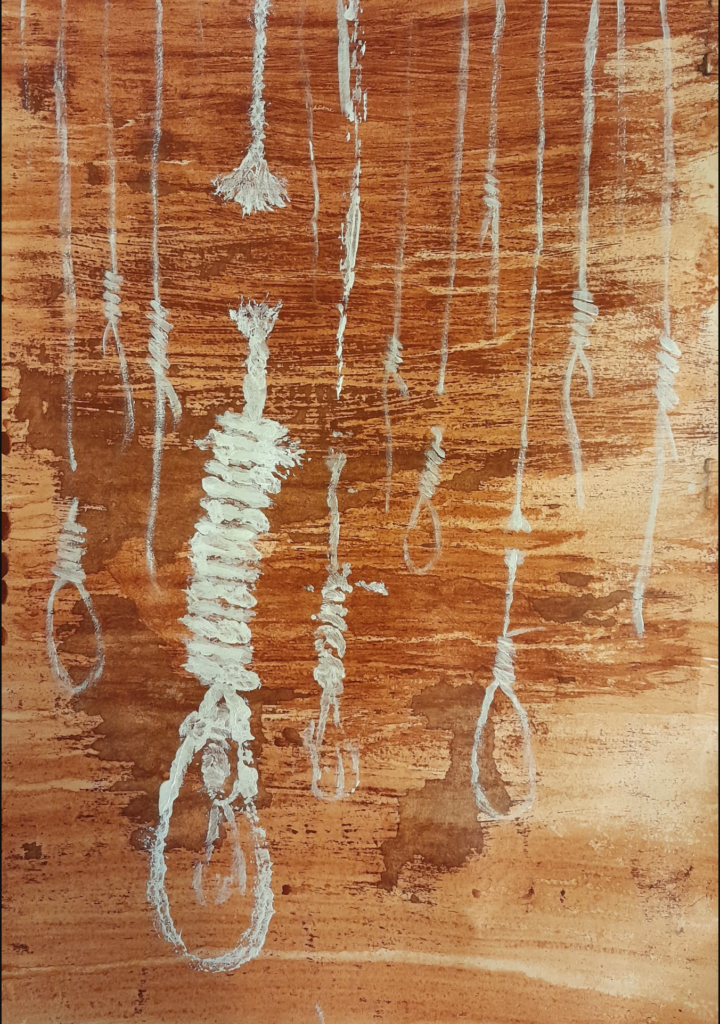

At first, I only wanted to show what had happened in prison, but now I have so many other ideas, I don’t have enough time to paint them all. My work explores the vulnerabilities of humans, of issues like refugee and women’s rights. I try and capture this in my work, regardless of the media I use, through drawing, painting, sculpture or print making.

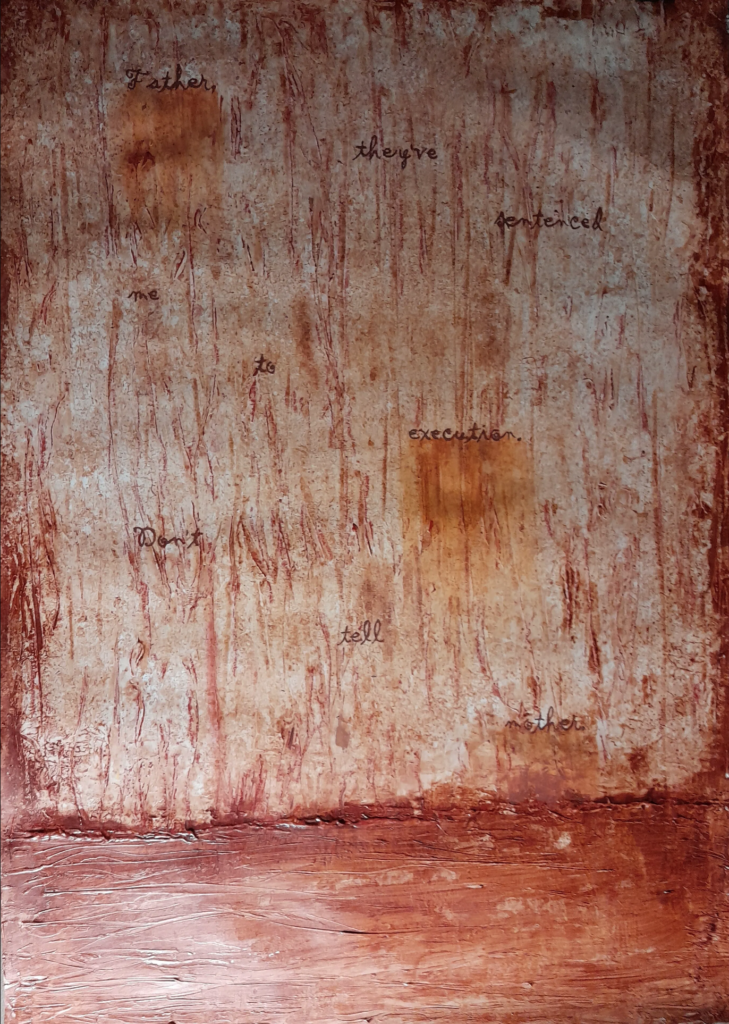

When I first got to the UK, my head was full of the scenes of prison. All I could think about were the faces of my friends who’d been executed, the noise of the firing squad and the crying of hungry children in the prison, the torture that we experienced, and the face of my father when I told him I’d been sentenced to death. Therapy helped me to slowly clear these images from my head, and over time, I was able to feel safe and strong again.

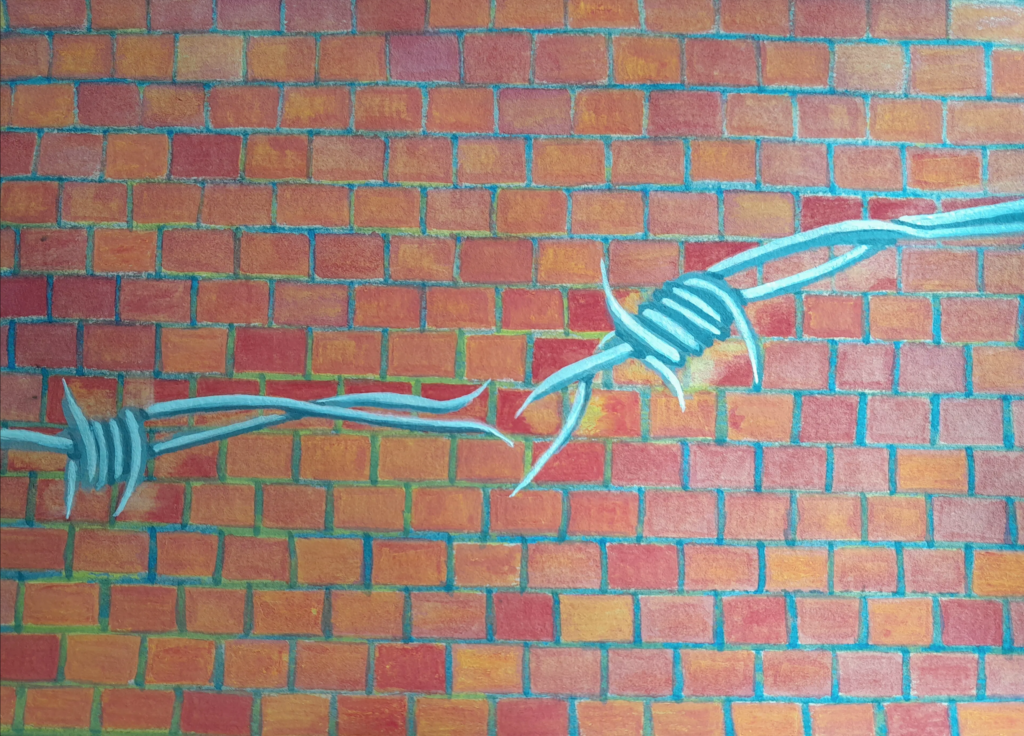

Still so many people in Iran have been imprisoned, they’ve been tortured and are languishing in prisons. I was lucky, I was able to get out. I’ve had the chance to recover and rebuild my life here in the UK. But my heart aches for the women who are still being subjected to the same kind of torture that I was. It’s horrific and depressing that this is still happening.

Iran is one of the top countries of origin of Freedom from Torture’s clients. There are many people like me who have fled their homes and reached the UK hoping just to live in safety. The therapists, lawyers and welfare advisors offer a lifeline to people who crucially need compassion, support and rehabilitation to recover.

Those in power in Iran now will do anything to try and suppress any opposition. Ex-prisoners, families of those still imprisoned, or anyone remotely politically active are being threatened and intimidated by security forces. It’s just more abuse carried out by an authoritarian regime that will stop at nothing to eradicate any form of defiance.

We need to continue to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the women and young people demanding the basic rights that we, in other parts of the world, take for granted and enjoy every single day. I’m calling on the international community and media to keep shining a spotlight on my country to demand that the regime stop using torture immediately.

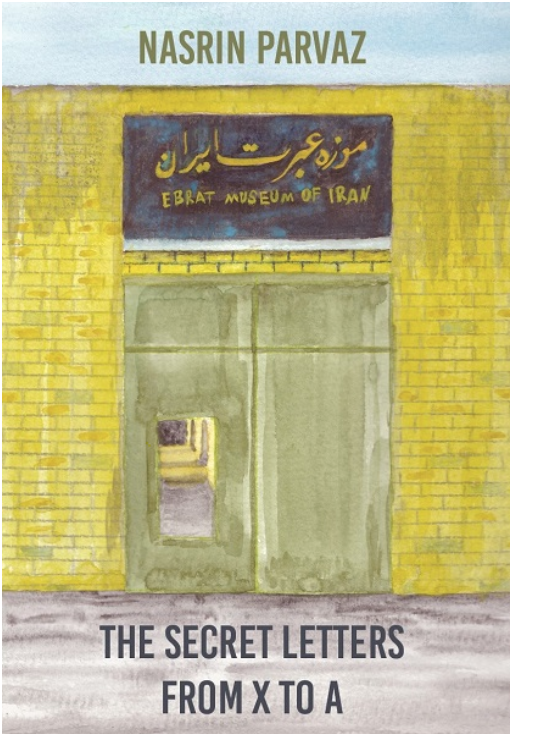

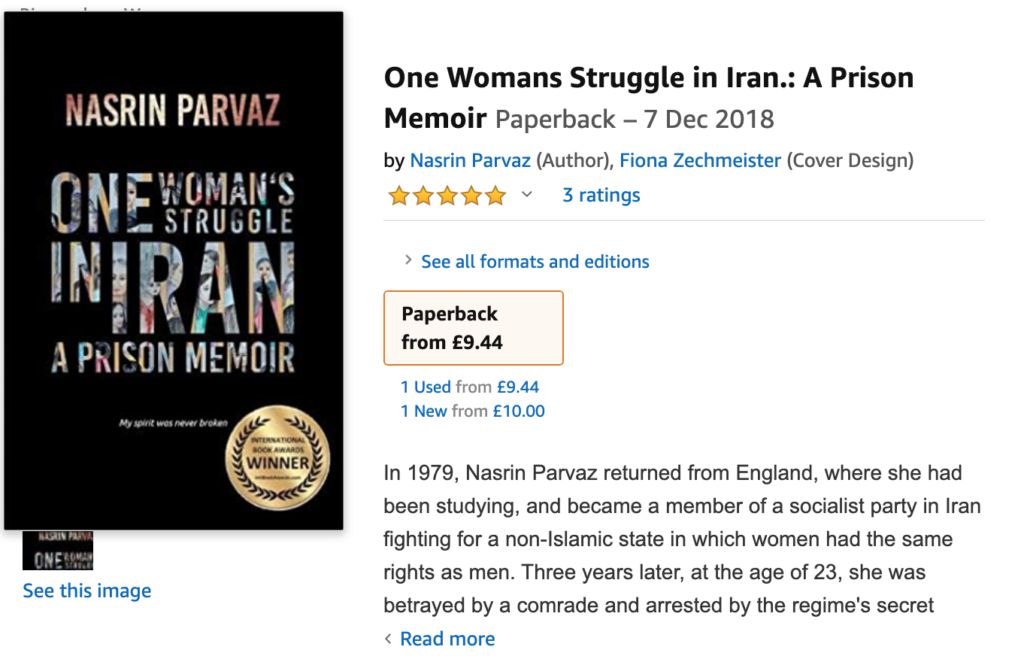

Nasrin Parvaz became a civil rights activist when the Islamic regime took power in 1979. She was arrested in 1982, tortured and imprisoned for eight years. Parvaz is the author of One Woman’s Struggle in Iran: A Prison Memoir and The Secret Letters from X to A.

Article originally appeared on Huckmag.

In 1979, Nasrin Parvaz returned from England, where she had been studying, and became a member of a socialist party in Iran fighting for a non-Islamic state in which women had the same rights as men. Three years later, at the age of 23, she was betrayed by a comrade and arrested by the regime’s secret police.

In 1979, Nasrin Parvaz returned from England, where she had been studying, and became a member of a socialist party in Iran fighting for a non-Islamic state in which women had the same rights as men. Three years later, at the age of 23, she was betrayed by a comrade and arrested by the regime’s secret police.

“For those of you who weren’t able to see it, it was an exhibition of paintings by foreign national prisoners and ex-prisoners, taken from a variety of sources. The exhibition was on display from the 1st to the 7th of May, and was opened by our MP,

“For those of you who weren’t able to see it, it was an exhibition of paintings by foreign national prisoners and ex-prisoners, taken from a variety of sources. The exhibition was on display from the 1st to the 7th of May, and was opened by our MP,