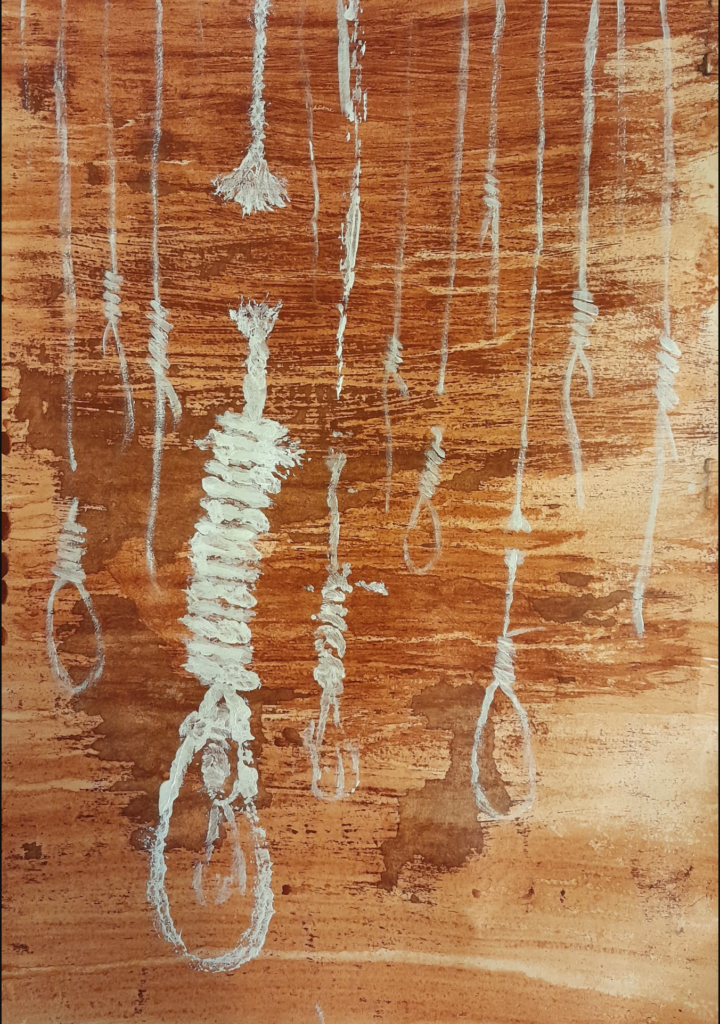

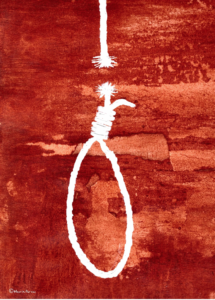

I can’t stop thinking about my fellow prisoners. People held in Evin have already suffered so much, and now this. For those of us who’ve been imprisoned, moments like this bring all the painful memories flooding back. All I can see are the faces of friends lost to executions.

For all of us – those still inside Iran or living in exile – these attacks are nothing short of psychological torture. Families wait in agony for news. Survivors like me relive their worst nightmares.

It’s been more than thirty years since I was imprisoned, but I remember it like it happened yesterday. I was held for eight years, threatened with sexual violence. And tortured. My ‘crime’? Speaking out against human rights abuses, state executions and women’s inequality. For this they called me a spy.

When I fled for my life, I left everything behind – my family, my friends, my home. Arriving in the UK, I had nothing. I felt so lost and alone. But I was lucky. I escaped. I’ve been able to heal, to rebuild, to find my voice again.

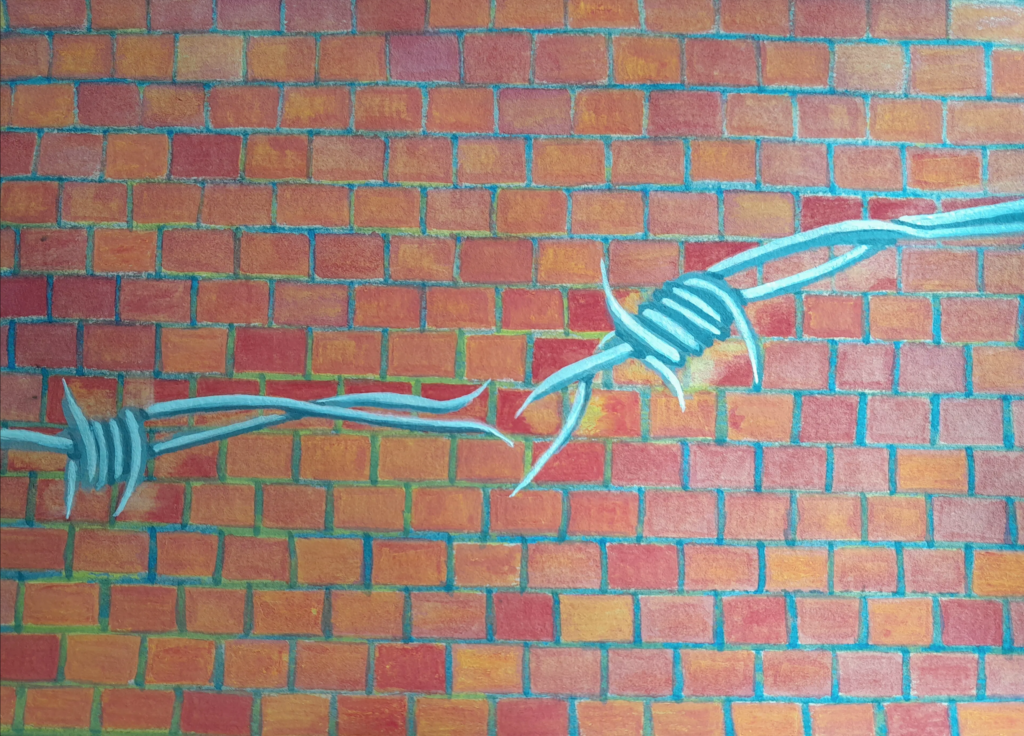

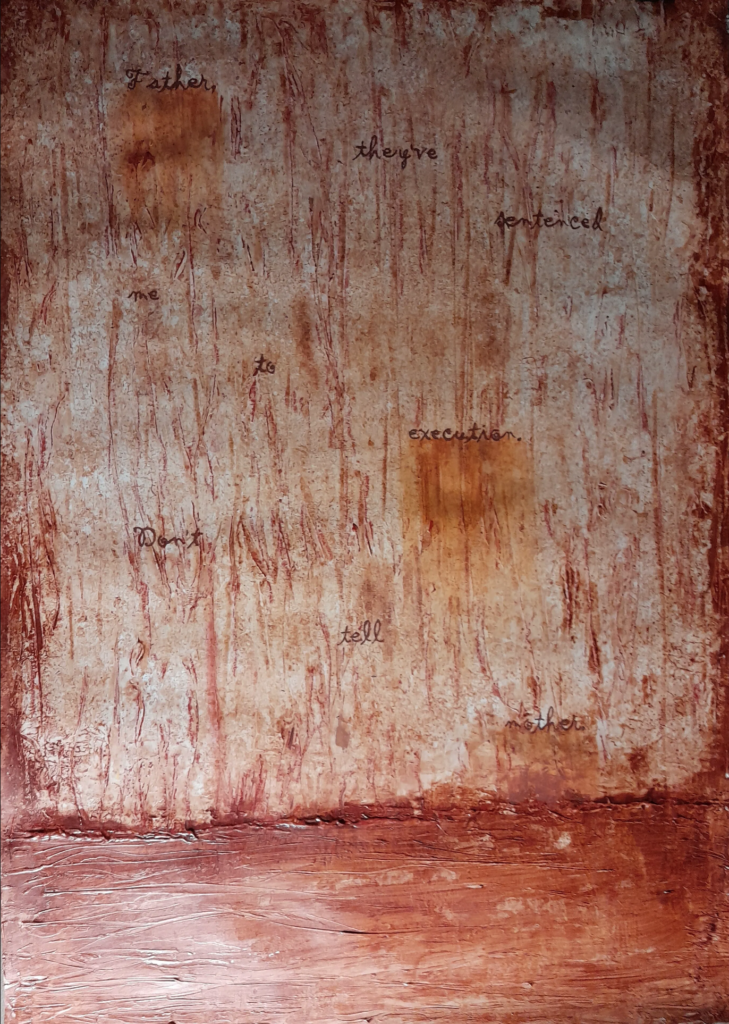

Now, I use my voice through writing, art, and activism. These are powerful tools for survivors like me. Sharing my story means I can raise awareness of the horrors still happening in Iran. Being able to do this has helped give my life meaning after everything I lost.

This year, on the United Nations International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, I stood with Freedom from Torture to unveil billboards across London, amplifying survivors’ voices. As conflict and repression escalate around the world, we’re calling for renewed public support to end torture.

My words now stand tall in Shadwell, East London: “I spoke out against executions in my country. I was tortured for it.” I am one of the lucky ones. I can stand here today and speak proudly and freely. But my heart aches for those still silenced, those being tortured for the simple act of standing up for what’s right.

The torturers tried to take my voice. But through therapy, writing and art, I reclaimed it. And now, our words are displayed for all to see. People need to understand why survivors like me are targeted: for standing up for basic rights, for falling in love, for dreaming of equality or just wanting to exist peacefully.

We’re asking the British public to stand with us – to welcome us as neighbours, as survivors, as people rebuilding our lives in safety. At this critical moment, when the UK Government threatens to weaken vital protections for survivors, we urge the country to stand firm: the absolute ban on torture must be upheld, with no exceptions. I believe the British people will choose compassion over cruelty. We need to remember that silence only helps the torturers, so together we must be louder.

________________

Nasrin Parvaz became a civil rights activist when the Islamic regime took power in 1979. She was arrested in 1982, tortured and imprisoned for eight years. Parvaz is the author of One Woman’s Struggle in Iran: A Prison Memoir and The Secret Letters from X to A.

LBC Opinion provides a platform for diverse opinions on current affairs and matters of public interest.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official LBC position.

Source: https://www.lbc.co.uk/opinion/views/tortured-iran-evin-prison-uk-survivors/