Out in the streets, hidden in the head to toe cloth, nobody recognized Mina, not even her closest family. Looking at the shop windows she saw her eyes at the top of a moving tent. The black sack disguised everything: her head, her face, her body and, equally, it would be the cover for her plan. Suddenly, she found freedom in that chador.

Mina created a questionnaire and asked a couple of the male students at her university, if they would help her with an experiment. Her research, she claimed, was to gain some insight into their relationships: how many women they had slept with, what sort of relationships they were looking for and had they ever found what they were seeking. But Mina really sought a different kind of access. All of the young men she approached made it clear they wanted to have sex with her, even before her questions were completed. She made one condition clear: each one of the men had to introduce her to one of their male friends first for the purposes of her research. She always met the men in the street. They would arrive in a car, pick her up then take her to a prearranged destination. Mina sat in the back of the car, posing as a passenger. The plan worked well.

And how would these strangers recognise her? She’d wear Red Glasses. She would laugh at her image in the mirror. Nothing else showed except the tip of her nose and her distinctive Red Glasses.

All the men were surprised once they realized she didn’t take money. ‘What, free sex?’ some of them would say. None of the men could accept the encounter as a one-off. They saw it as part of their male birthright to dictate the terms of a relationship with a woman. Any attempt to challenge their masculinity would threaten their manhood deflating it, like a balloon popped with a needle. To get away easily, she always took their numbers, promising to call. But she never did. She recorded their names and telephone numbers in her notebook, each on a separate page. Then, beneath each name, she wrote down what distinguished that man from others. She’d write in the third person, using only their initials in case her parents went through her private things and found the notebook.

A took her to his friend’s room. He sweated profusely.

H asked her to walk several paces behind him so his neighbours would not see them together.

R talked a lot.

M was witty and managed to make her laugh.

B breathed so heavily and with such difficulty, she thought he might die at any minute.

S made noises like a motorcycle and confided he was a virgin.

D was curious about her. He asked her lots of questions, as if he were the researcher.

E smelled like cooked cabbage. He wanted more of her.

F craved nurturing, wanting her to take her time to touch and caress him.

G had bought pizza before picking her up and asked her to eat with him but she refused. She watched as he wolfed down the entire pizza, smearing it around his mouth in greed. When he sat closer, traces of cheese and tomatoes and red pepper dropped from his lips. She asked him to rinse his mouth. He did, like an obedient child.

C fell in love with her. He begged her not to see other men, only him. But would he marry her, she asked? Not that she wanted to marry him or that she particularly liked him even. She just wanted to find out what kind of man he was and his response would speak the truth. But he avoided the question. Yet he did warn her to be careful: everywhere, men were talking about the Woman in the Red Glasses.

As her experiment went on, Mina discovered that each man had his own unique form; how his fingers felt on her body; the way he talked, even his silence revealed so much. Some didn’t recognise her or even acknowledge her as human. Some of the men just wanted to fuck her, leave and get on with their lives. It intrigued her to see how each man had different ways of trying to impress her. Some insisted on seeing her again under the pretence of having something important to tell her. But she knew each time that they were only thinking and talking with their under bellies.

Each man’s sweat smelt different. She wondered how similar their scent would be if they’d all eaten the same food or washed themselves with the same soap or shaved with the same balm or wore the same aftershave? After the first, loveless experience, she bought the aftershave Mehdi had worn. She told each man to put the scent on before allowing them near her. But it made no difference; none of them had smelled like her Mehdi. No amount of cologne could mask their repellent smells. During the act of sex, she observed the noises they made and the way they came. Yet none gave her any of the pleasure Mehdi had. None of them could. She pressed on, the pages filling up by the day soon she had to buy a second, then a third notebook.

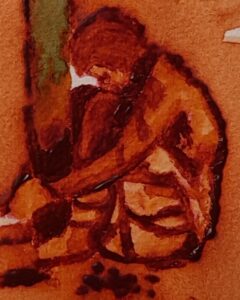

Mina could see the vulnerability in all of them, despite the image of superiority they tried to project. When naked, they would regress back to their babyhoods, desperately attempting to return to the comforting, female ocean from which they’d burst forth: their mother’s womb. And at the point of their orgasm, they’d kick her belly with their third leg, like a baby kicks out within the confined safety of his mother’s tummy.

Afterwards, she’d wanted to tell them how little they understood women and how ignorant they were about how to make love to a woman and treat her properly. And how they truly were missing much greater pleasure than they could imagine. They were always in a rush; the same rush as when they ate; no savouring of their food or its taste, smell, or beauty (or ugliness, even). No recognition of the time taken in its loving preparation. They just shoved it down thoughtlessly with their stagnant, immature urge for instant gratification. And they consumed women in exactly the same way. These men joked that just as they didn’t like eating the same food every day, no matter how delicious, they wanted variety in their women, too. And they viewed her like a side-dish; an alternative on the menu, something they were entitled to. It didn’t matter if this food was alive and breathing and felt pain under their second mouths. And through her encounters with these dual-mouthed creatures, she tried to obliterate her loss.

As the days went by, with or without the men, her mind turned to her lover, Mehdi, and their last conversation echoed in her head.

‘Will you marry me?’ He asked.

‘I’d have to escape my parents to be with you.’

He had kissed her, ‘I expect your father wants to marry you off to one of those minister’s sons.’

‘Yes. He’d be happy to marry me off to one of those criminals.’

Before she had met Mehdi, Mina had never liked politics. Her father was a minister. She believed all politicians were hypocrites, including her father and all his friends and peers, using their positions and politics to climb a corrupt ladder to wealth and fame.

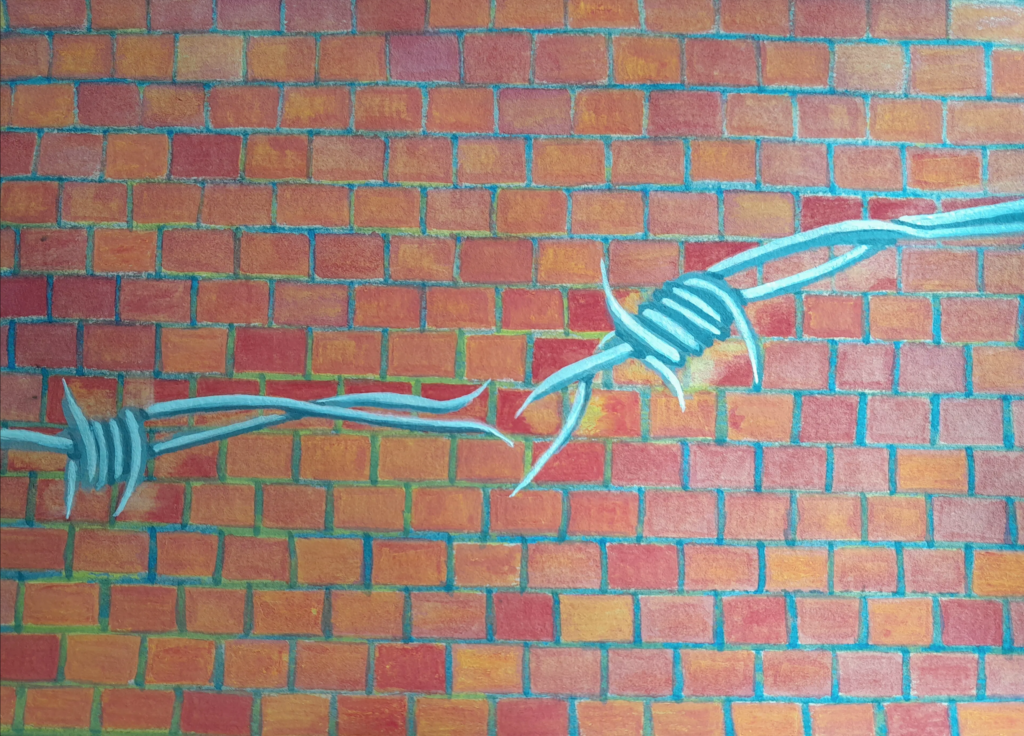

‘But how can we defend our rights without engaging in politics?’ Mehdi once argued.

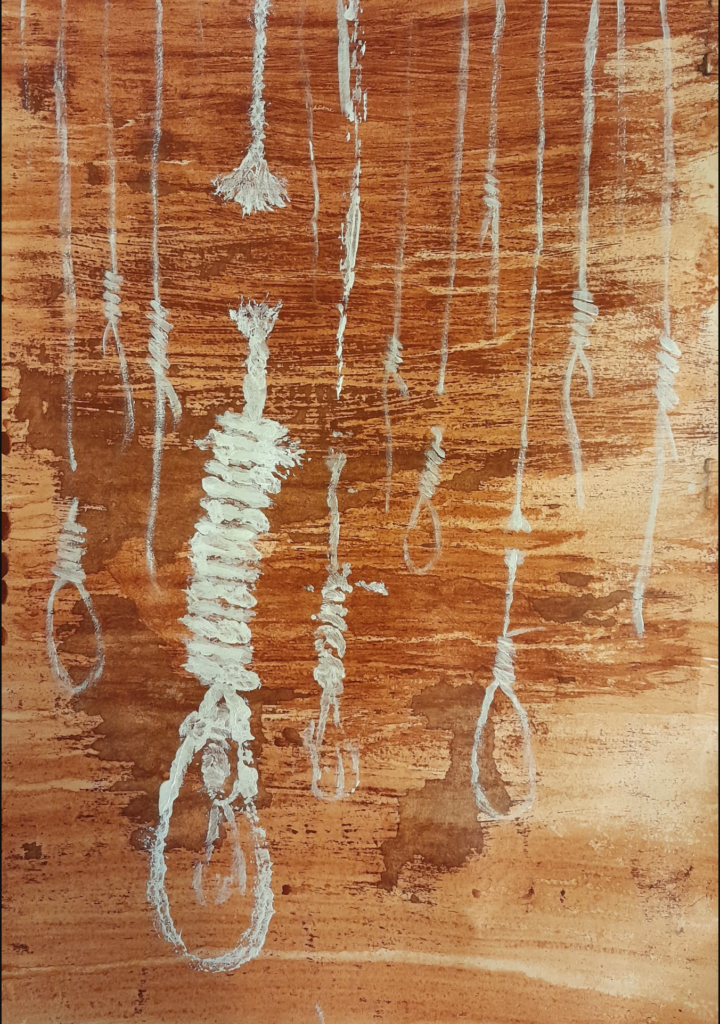

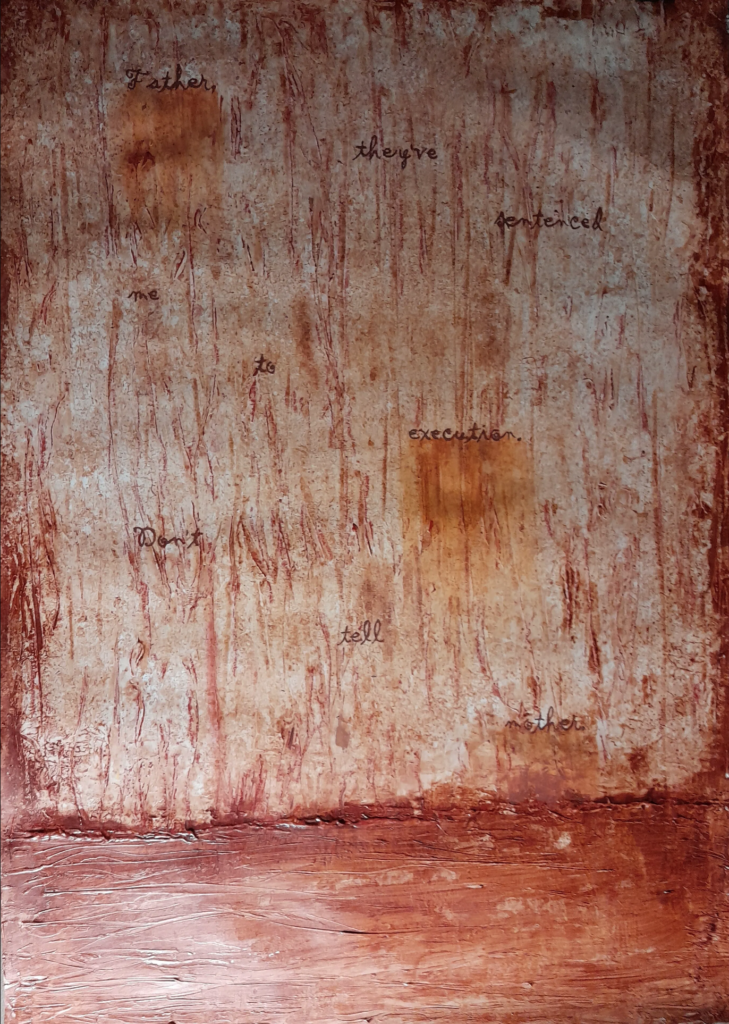

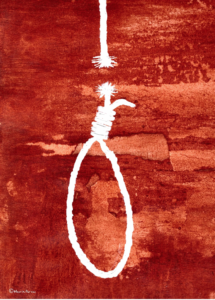

During their friendship, Mina learned that it was Mehdi’s politics that made him the man he was; the man she would love forever. His politics hadn’t brought him wealth or status; he’d simply never sought these things. His politics had brought his death; all because he’d believed the world was rich and abundant enough to ensure that no human being need ever go hungry or go without. News about the execution of dissidents had always made her angry. But when she lost Mehdi, it felt to her as if her own father, the great minister himself, had put the noose around her true love’s neck.

Mina became engulfed in hatred for her father. In his world, the worst thing a woman could do was sleep with men. And through her actions, Mina created a double life; a life that she could never have possibly imagined before losing Mehdi. And the more she slept with these strange men, the more she became a stranger in her father’s house.

She pondered before each new meeting. What would this one look like? Where will he take me? Will he be different; the one who will finally see me, really see me and respect me? With each new encounter, she wondered whether she’d be able to bear it and see the act through to the end. Or would this be the one where she’d feel so sick that she couldn’t take any more and be overwhelmed and long to flee? Would she be in danger of being beaten or killed? She no longer cared. By their very actions, these men had killed off the memory of Mehdi that she had carried inside her. Now that her lover had become an unreachable shadow in her mind, she felt so empty that she needed these men to fulfil her life.

One afternoon she stood in the usual place, waiting to do battle again. She watched out for the agreed signal: the car horn sounding three times, the car pulling up beside her and the rear passenger door opening. As always, she wordlessly climbed in making no eye contact with the driver. The car pulled away. The split second before the man spoke, she felt it: his stifling familiarity and his cologne, dominating smell. She knew. Then she heard it: her father’s voice.

‘I heard you are very beautiful.’ His eyes studied her in the car mirror. ‘Show me your face.’

She realised that this was not their usual family car, but a different vehicle; her father did not recognise his own daughter. And she knew what her father saw: not another human being, but a mere collection of female body-parts. She was nothing more: just a variation from the regular menu, there to be consumed at his whim, like any other delicacy.

And when her father realised that the Woman in Red Glasses was not the faceless woman he had picked up in his secret car, what would he do? Would he put a rope around her neck? Or would he wash his hands of her and pass her over to the police; let them deal with her, finish her off? She didn’t know. But one thing she was certain of: her death was near.

Since Mehdi’s death, in losing one man, she could gather all men. Now her own father had become part of her macabre collection. Looking back, she could see how all these men scavenged her, and little was left for her father to destroy in order to maintain his reputation. There was nothing left for her in the world now; nothing left but to die, just as her beloved Mehdi had died before her.

The traffic lights changed and the car came to a standstill. Here was a chance. She could jump out and run away and stay anonymous, just as she had entered this car and every other single car before.

Her father spoke to her, his voice riddled with lust. ‘You seem shy. I’m going to have a good time with you.’

She raised her head and looked directly into the car mirror, her dead eyes locking with his. As she pulled at the chador, casting it away, she realised she was hiding from herself as well as others in it. She threw off the Red Glasses. ‘Yes. I’m sure you are, Father.’

https://www.unlikelystories.org/content/woman-in-the-red-glasses