Inside Stories: stories of resilience during the pandemic is a series of conversations with people who have been displaced by war, conflict or persecution about their lives, thoughts and hopes for others.

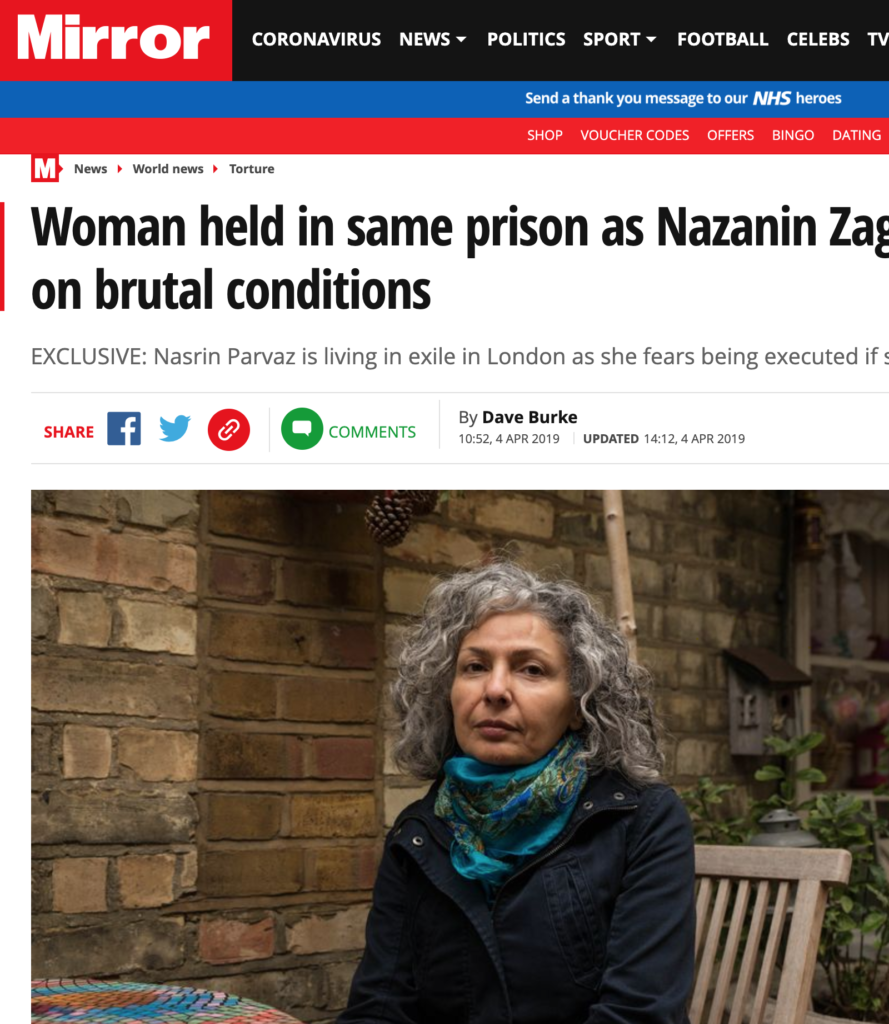

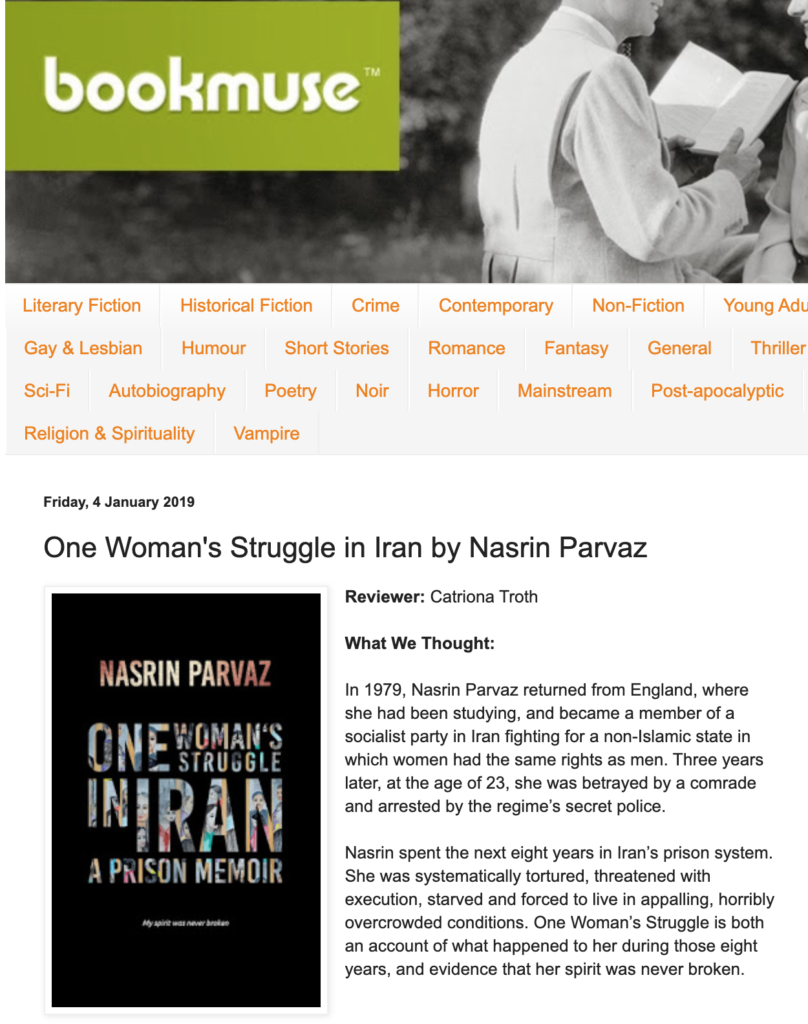

As a young woman in post revolutionary Iran, Nasrin Parvaz was arrested for her political activism and spent the next eight years in Iran’s prisons. The brutality of the prison regime, her friendship with her fellow women prisoners and their children, and the unexpected glimmers of joy and humour are captured in her book, One Woman’s Struggle in Iran: a prison memoir. Nasrin was granted protection in the UK in 1993 and is an author and artist. She continues to campaign for justice and is an active members of Survivors Speak Out at Freedom from Torture.

A few weeks into the lockdown, we asked Nasrin what has happening in her life, what was on her mind and what message she might have for others.

“My life hasn’t changed much. Due to epilepsy, which I developed as a result of having my head bashed against walls in prison, my social life had become limited the last few years even before the pandemic; that means I couldn’t do the activities I would have liked. So my life was mostly dedicated to writing and recently to art. Now with the lockdown, that little social life that I had is gone and I’ve missed it, but I’m in touch with friends by phone. I’m very grateful that my editor has finished editing my most recent novel during the lockdown and with that aside, I now have other unfinished books to work on, and I continue my art classes on Zoom to improve my painting.

However I’m aware that this situation is very hard for people who have lost their loved ones, or for those who lost their jobs and don’t have a secure future. At the same time there is money available, it’s just not given to those who need it, and this hurts me. Especially when everyone had to stay at home and look after themselves and the construction workers still had to work. A friend of mine who had done many different jobs and who is a construction worker, worked until he dropped to the floor with the coronavirus and was under ventilation for 12 days. When he came out of the ICU the nurses clapped for him, saying he fought for his life. He had no energy to tell them that they had saved his life.

Once more this situation has reminded me that my struggle for justice was right and that I have to continue. Last year there were multiple floods in Iran that made so many people homeless. Flooding also happened in numerous other countries and it only makes the poor poorer, whilst the rich, whose companies heat up the earth producing useless goods, get richer.

The situation reminds me of prison, but not solitary confinement where I was deprived of being able to see anyone for days and nights for months. It reminds me of times that we prisoners were together or in different rooms, but had no right to talk to each other. We would be tortured if we did. Yet the guards could not read our eyes and a glance at my cellmate meant I had written a letter for her. We had secret places where we used to hide our letters. When another friend of mine hung her blue shirt on the washing line, I knew she was telling me that she had hidden a letter for me. An ordinary book would be a cover for our little letters to read under the guard’s nose. Just as we found new ways to communicate in prison, we are now using social media to be in touch with each other.

I hope this situation opens our eyes and people try to change the world for a better future. I’m worried that big pharma may attempt to capitalise on the importance of the virus and extort people by profiting on the price of the vaccine.

Nasrin Parvaz, June 2020

One thing that kept me going in prison was the belief that the situation will pass. I believed nothing was permanent and it’s the same with this situation we’re living in now. One day this virus will disappear. But I hope this situation opens our eyes and people try to change the world for a better future. It makes me sad that all the production is for profit rather than for people’s benefit – and everywhere people become poorer and a select few get all the wealth with the help of the system and army that they have made to protect themselves. I’m worried that big pharma may attempt to capitalise on the importance of the virus and extort people by profiting on the price of the vaccine if it is successfully developed.

I also hope all those polluting cars won’t come back to the streets, and that there is a solution. If transport is public and free, not for profit, then people would not bring their cars to the street and the air wouldn’t get polluted: the earth would breathe rather than burn as it does now.

#CommunityAcrossDifferences #RefugeeAllies #InThisTogether #InsideStories

© Milan Svanderlik for www.LondonersAtHome.org

In 1979, Nasrin Parvaz returned from England, where she had been studying, and became a member of a socialist party in Iran fighting for a non-Islamic state in which women had the same rights as men. Three years later, at the age of 23, she was betrayed by a comrade and arrested by the regime’s secret police.

In 1979, Nasrin Parvaz returned from England, where she had been studying, and became a member of a socialist party in Iran fighting for a non-Islamic state in which women had the same rights as men. Three years later, at the age of 23, she was betrayed by a comrade and arrested by the regime’s secret police.

“For those of you who weren’t able to see it, it was an exhibition of paintings by foreign national prisoners and ex-prisoners, taken from a variety of sources. The exhibition was on display from the 1st to the 7th of May, and was opened by our MP,

“For those of you who weren’t able to see it, it was an exhibition of paintings by foreign national prisoners and ex-prisoners, taken from a variety of sources. The exhibition was on display from the 1st to the 7th of May, and was opened by our MP,